Hello, readers! Those of you who have been following my blog closely (and who wouldn't? I know you read it religiously and check every hour for an update. We can keep it our little secret.) may have noticed that I haven't updated at all this week. The simple answer is that, since I was on my school's band trip to Disneyland, I couldn't update. The longer, more embarrassing reason is that I had a post planned, and then just completely forgot about it. So, sorry about that! I'm going to write a really long entry here to make up for that.

So, what will this super-long post be about? Gluten-free diets.

Go into any grocery store. Or any cookbook isle in a bookstore. The number one diet that seems to be advertized the most (that stands out to me, anyway) is gluten-free cooking. One of the huge selling points of a lot of foods now is that it's gluten-free.

We've got gluten-free pancakes,

gluten-free brownies,

and various other gluten-free accoutrements.

So, obviously being gluten-free is really popular. But what, exactly, does "gluten-free" mean? What even is gluten anyway??

|

| Pictured: the mythical and mysterious gluten fairy. No one knows who she is or what she actually does. |

Gluten is actually a protein made up of two different substances (called

gliadin and

glutenin, for those who are interested) that is bound to the starch in many plants. For human (i.e. dietary) purposes, the main thing we associate with gluten is wheat.

Now, for some people, eating gluten is actually very dangerous. People who have celiac disease

really shouldn't eat any gluten. Celiac disease is a genetic autoimmune disorder, which means that, in a similar way to arthritis, the body's own immune system attacks itself. While arthritis results in painful joints, celiac disease can actually be very dangerous if you're not careful. If you have this disease and eat any gluten, the body begins to attack the lining of the small intestine, destroying it if the process continues for too long.

In recent years, there have been studies conducted about the possible existence of "gluten sensitivity." Basically, a theory exists that different people tolerate gluten differently and it is more harmful to some people than others, but this theory is largely speculative and there have not really been any major conclusions.

|

| Great job, science. |

If you have celiac disease or are gluten intolerant, you can ignore what I'm going to say for the rest of this post, since (spoilers) I'm going to argue that eating gluten really isn't all that bad for you, and it's healthy for a completely different reason than you think.

Let's go off on a tangent for a little while here (bear with me). Why do you have to inject insulin subcutaneously if you're diabetic? Why do you have to go to all the trouble of getting out a needle and injecting it when you could just swallow it or something?

|

| Needles are scary, okay? |

Like most substances produced by the body, insulin is a protein. Proteins really can't be taken orally because the body's digestive system (saliva, stomach, and intestines) break up any proteins you eat into their component parts (amino acids) to be recycled in other bodily functions, like gluconeogenesis, which I've mentioned before, and forming new proteins. So you really can't use insulin if you ingest it because your body breaks it up, just like it would a juicy steak.

|

| Alas, not the cure for diabetes. |

So, if you reach back around for the actual point of this tangent, you can see that gluten is a protein bound to starch. If your body eats a protein like gluten, it breaks it down into amino acids just like it would any other protein, which means that gluten really doesn't hang around and wreak havoc in your body. It's just treated like steak. Again, you should ignore this when dealing with gluten intolerance or celiac disease.

But, Emily, you might say. I know people who are eating gluten-free, and they're so much healthier! They've told me it's so much better, and they've lost weight! I will simply answer, remember how gluten is bound to starch in plants like wheat? Starch,

|

| This ugly thing. |

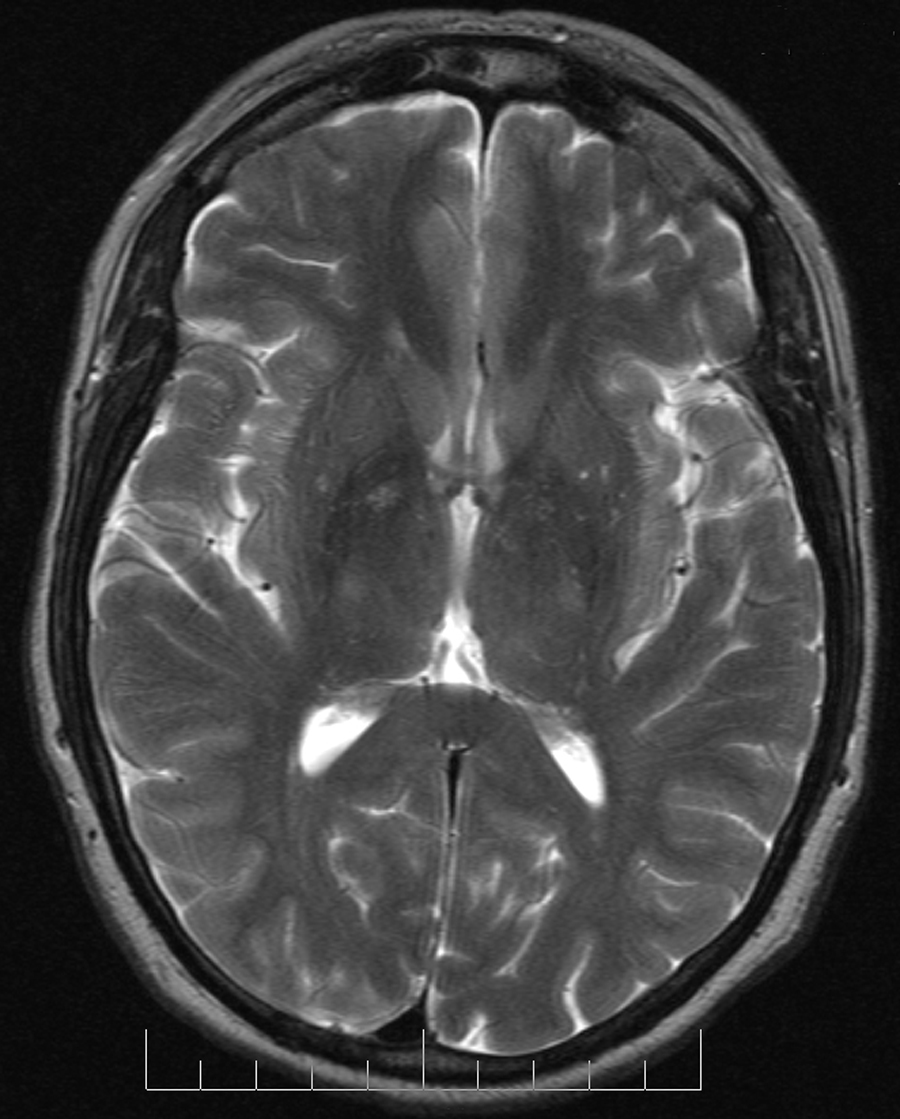

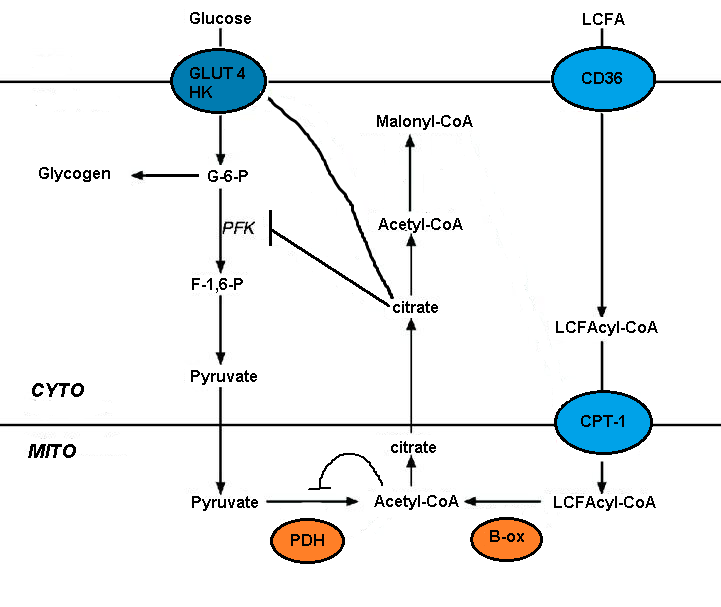

is a more complicated form of a carbohydrate. Aka, glucose, the bad guy. A large component of following a gluten-free diet is avoiding eating any grain products unless they are gluten-free. This limits your options somewhat, so the overall volume of grains (carbs) goes down. Since you're eating less carbs, you ingest lest glucose, which means you have less citrate leak (remember that fun graph?), and gain less weight while possible even burning some off if you go into ketosis. So it's really just a case of false correlation: you start to eat gluten-free, which means you're eating less carbs, and you get healthier--so you attribute it to eating gluten-free rather than just eating less glucose. Technically, what I'm doing right now is gluten-free, but I'm learning it's because of the carbs and not fat or gluten.

Some people have the opposite problem, though. A lot of people end up gaining weight when they eat gluten-free because they substitute all of their bread and grain foods with products that come from corn and potatoes, which are also really starchy, which is the problem in the first place.

|

| Still the silent killer, but for a different reason than previously thought. |

So, basically, if you want to eat healthier, gluten is pretty much fine, as long as you just avoid any huge amount of glucose.

Thanks for reading!